A former B-school dean boosted his school’s rankings by fraudulently misstating student test scores, work experience, and other data. If rankings weren’t crucial, he wouldn’t have done it. But might such rankings also be meaningless?

Ranking Mania

The last 30 years have seen an explosion of rankings. Among other things, we rank countries for rule of law, economic freedom, freedom of speech, innovation, etc. We rank for-profit companies for size, creditworthiness, sustainability, and the like.

Perhaps the most influential rankings of educational institutions are carried out by U.S. News and World Report (“U.S. News”). How influential? Well, former Temple University Business School Dean Moshe Porat has ruined his reputation and career, and may lose his freedom, by lifting his school’s online-MBA program to the top of the U.S. News list through fraud.

Rankings have certainly become crucial. But, if we dig into the methodologies they employ, how often might they also prove meaningless?

The Emperor’s New Clothes

Rankings bring notoriety, prestige, and revenue to the organizations that produce the rankings. Rankings also drive the careers of people who run governmental, for-profit, and educational institutions. This in turn drives institutional behavior.

Many, many billions of dollars are at stake. Increasingly, rankings are baked into regulations and decision-making processes. Bad rankings can get companies — and even countries — blacklisted.

But how much thought — and independent oversight — go into assessing these methodologies? Once a government or industry has baked a particular ranking into its processes, how readily and fairly will re-evaluation take place?

We also know that special interests thrive on tweaking or warping standards to their benefit. What forces work against favoritism and corruption?

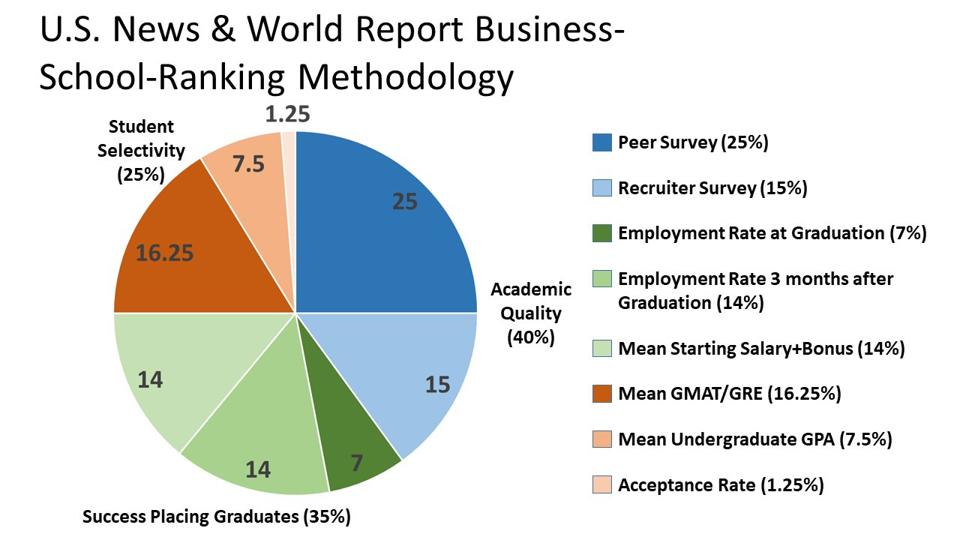

The U.S. News Methodology for Ranking MBA Programs

The following graphic lays out the major categories of U.S. News’ methodology for ranking full-time MBA programs. Additional information on US News’ ranking of graduate schools generally can be found here.

For this column, U.S. News declined to answer questions regarding its methodology. Nor would U.S. News make available copies of its surveys, nor provide details, other than to reference the links cited above.

Academic Quality (40%)

Academic quality makes up 40% of U.S. News’ ranking. This category appears wholly subjective, comprising survey responses from MBA Deans and Directors (25%), as well as corporate recruiters (15%).

- Details of U.S. News’s Methodology

For 2022, U.S. News sent out 486 surveys, received 364 responses, and ranked 143 schools.

The survey asked respondents to rate the MBA-program-quality of other schools on a scale of 1-5. Respondents may also state they lack sufficient familiarity with a program to answer.* U.S. News takes the average of survey scores from Deans/Directors and a weighted average score for recruiter-submitted surveys over the past three years.

Surveys often repackage subjective — and unreliable — opinion as quantified data. Could that be the case here?

A 1-5 scale tightly compresses evaluations. Also, the methodology does not describe any criteria given to respondents to normalize their assessments, nor any guidelines on distributing scores. For example, can a respondent give 40% of the schools a five? 60%?

MBA-school deans and directors might be assumed to keep a watchful eye on their nearest competitors. But will such people evaluate these competitors fairly? And how far out does respondents’ knowledge reliably extend?

What about recruiters? What qualifies them to assess MBA programs? Behavioral economics might predict that recruiters will subconciously substitute a question they cannot answer (“Assess MBA-program quality”) with one they can (“Assess the quality of candidates they have seen from various MBA programs”). These are two very different questions.

In sum, 364 responses of uncertain consistency and accuracy drive 40% of MBA-school rankings.

Does that seem sensible?

Does it seem fair?

- Possible Alternatives

If current surveys shed little light, what might work better? First off, US News might apply factors the schools themselves use for faculty promotion and recruitment: publishing success. In other words, who is publishing, in which journals, and with how much subsequent citation by other academic writers?

In addition, U.S. News might track the movement of faculty from one B-school to another when careers are on the upswing and/or decline. Who poaches other schools’ top performers, and which schools’ top performers get poached? If someone at a particular school fails to get promotion or tenure at a particular school, where does he or she go?

The above alternatives can comprise a fuller set of data. B-school websites typically provide faculty CVs, which include publishing and employment histories. Publishing success and job movement can be fed into an algorithm, which will be consistent and can be adjusted over time after open discussion.

Finally one might look at conversion rates (percent of students admitted by a school who then matriculate to that school). Where a student was admitted to multiple schools, which one did the student select, and which one(s) did he or she reject?

Success Placing Graduates (35%)

Success placing graduates touches upon employers’ assessments of MBA programs, as well as the return on investment students can expect from their educations.

Mean student starting salaries and bonuses (14%) go to these questions. But, using the mean gives more weight to outliers, high and low. Using the mean also punishes programs that place graduates into lower-paying public-sector or non-profit fields, or lower-paying geographies. Here, it might make more sense to look at median starting salary+bonus, adjusted for tuition costs and local cost of living.

Other placement factors (i.e., employment rates (7%) at and three-months after graduation (14%)) seem like a low bar and poor proxy; they focus on the worst 5-25% of students. A more interesting ROI question might be median student salary five years after graduation, taking into account inflation-adjusted tuition and local cost of living. After all, relatively few students worry about getting some kind of job after graduation. Nearly all of them worry about paying off student loans and establishing career trajectory.

Student Selectivity (25%)

In this category, U..S News focuses almost entirely on grades, whether GMAT/GRE scores (16.25%) or mean undergraduate GPA (7.5%). Program acceptances rates account for a smidgeon (1.25%).

There’s irony in such heavy reliance on grades. Business schools champion their nuanced and individualized selection processes, as well as their pursuit of diverse, equitable, and inclusive student bodies. U.S. News seems to throw these factors out the window. Why don’t the schools protest?

At the same time, measuring acceptance rates encourages B-schools to flirt. They need to attract as many applicants as possible to maximize the number of times the Admissions Office can swipe left. In addition, schools may shy from the rankings hit of admitting students who have demonstrated talent and character but whose board scores and/or GPAs are low.

Finally, Selectivity as currently measured overlaps with Success Placing Graduates. How hard will it be to place graduates who entered B-School with top board scores and perfect (or near-perfect) undergraduate GPAs?

Just One More Thing…

What in U.S. News’ methodology, or these comments on it, deals with quality of education? It’s possible, for example, for academically brilliant faculty to fumble at teaching students or otherwise readying them for the world of work.

Conceptually, educational quality means the school augments students’ knowledge, skills, habits, and character. In a sense, this is the positive difference between:

- Quality of Input (as measured by Student Selectivity); and

- Quality of Output (as measured by Success Placing Graduates)

Measuring educational quality this way supports using median graduate salaries five years after graduation, rather than employment rates at (and three months subsequent to) graduation.

Getting What You Pay For

People ofttimes pay for the brand rather than the product. They’re welcome to do so. But, they shouldn’t mistake one for the other.

In a rankings-mad world, we need to look hard at the people and the methodologies doing the ranking. A quick review of U.S. News’ approach to B-Schools raises legitimate questions.

With regard to rankings of any kind, we owe it to ourselves to dig deeper and to look harder. Otherwise, we risk making crucial decisions based on meaningless data.